Linear regressions

Tips before you start:

-

You can pull up documentation for a function by executing

?function_name(e.g.?t.test) in the Console. -

You might want to start a new .Rmd file for this activity

-

Throughout this workshop, instead of typing in commands directly in the command line or in the code editor, type them in chunks of code in your .Rmd file.

-

Now that you are bit more familiar on how to use .Rmd files,there are some additional tips that make it using .Rmd files easier:

- You can run each individual chunk of code all at once by clicking on the little green arrow facing right at the top right of each chunk:

- You can run all chunks of code above by clicking on the little gray arrow facing down at the top right of each chunk:

- You can decide if you want R Studio to output the results of each chunk of code inline in your R Markdown file, or in the console. This is just for when your are actively working on the file, when knitting, all outputs appear right after the chunk of code. To decide, click on the setting buton on the right of the knitting button, and select the option you prefer.

- You can run each individual chunk of code all at once by clicking on the little green arrow facing right at the top right of each chunk:

-

Finally, have the tidyverse package installed and loaded in RStudio before you start this activity:

# only need to run once in the console if tidyverse not installed: install.packages('tidyverse')

library(tidyverse)

- If you need a reminder on data manipulation functions, check out the dplyr cheat sheet

Download data

In this activity, we will build linear models to predict life expectancy with one or more independent/explanatory variables. Download the Life Expectancy dataset by right clicking on this text and select “Download linked file as”. Save it in the same folder as your current R Markdown file.

The source of this data is this website.

Import the data

Import the dataset by typing the following in a code chunk, and then sending it to the command line:

# Import data

life_expectancy <- read.csv("WHO_Life_Expectancy_Data.csv") # change to the appropriate file path to the downloaded dataset on your computer

Let’s then preview the data to see if it was uploaded correctly (paste the code below in a chunk of code and then send it to the command line). As you can see, the data shows multiple variables possibly related to overall life expectancy for different countries over the years.

head(life_expectancy)

## Country Year Status Life.expectancy Adult.Mortality infant.deaths

## 1 Afghanistan 2015 Developing 65.0 263 62

## 2 Afghanistan 2014 Developing 59.9 271 64

## 3 Afghanistan 2013 Developing 59.9 268 66

## 4 Afghanistan 2012 Developing 59.5 272 69

## 5 Afghanistan 2011 Developing 59.2 275 71

## 6 Afghanistan 2010 Developing 58.8 279 74

## Alcohol percentage.expenditure Hepatitis.B Measles BMI under.five.deaths

## 1 0.01 71.279624 65 1154 19.1 83

## 2 0.01 73.523582 62 492 18.6 86

## 3 0.01 73.219243 64 430 18.1 89

## 4 0.01 78.184215 67 2787 17.6 93

## 5 0.01 7.097109 68 3013 17.2 97

## 6 0.01 79.679367 66 1989 16.7 102

## Polio Total.expenditure Diphtheria HIV.AIDS GDP Population

## 1 6 8.16 65 0.1 584.25921 33736494

## 2 58 8.18 62 0.1 612.69651 327582

## 3 62 8.13 64 0.1 631.74498 31731688

## 4 67 8.52 67 0.1 669.95900 3696958

## 5 68 7.87 68 0.1 63.53723 2978599

## 6 66 9.20 66 0.1 553.32894 2883167

## thinness..1.19.years thinness.5.9.years Income.composition.of.resources

## 1 17.2 17.3 0.479

## 2 17.5 17.5 0.476

## 3 17.7 17.7 0.470

## 4 17.9 18.0 0.463

## 5 18.2 18.2 0.454

## 6 18.4 18.4 0.448

## Schooling

## 1 10.1

## 2 10.0

## 3 9.9

## 4 9.8

## 5 9.5

## 6 9.2

Prepare the data

We are going to use only data from the year of 2015 as it is most recent. For this, use the filter()function from dplyr (i.e.g, part of the tidyverse package), which we cover in the workshop Introduction to RStudio. Paste the code below in a chunk of code and then send it to the command line:

# Filter the dataset

life_expectancy_2015 <- life_expectancy %>%

filter(Year == 2015)

# Check results

head(life_expectancy_2015)

## Country Year Status Life.expectancy Adult.Mortality

## 1 Afghanistan 2015 Developing 65.0 263

## 2 Albania 2015 Developing 77.8 74

## 3 Algeria 2015 Developing 75.6 19

## 4 Angola 2015 Developing 52.4 335

## 5 Antigua and Barbuda 2015 Developing 76.4 13

## 6 Argentina 2015 Developing 76.3 116

## infant.deaths Alcohol percentage.expenditure Hepatitis.B Measles BMI

## 1 62 0.01 71.27962 65 1154 19.1

## 2 0 4.60 364.97523 99 0 58.0

## 3 21 NA 0.00000 95 63 59.5

## 4 66 NA 0.00000 64 118 23.3

## 5 0 NA 0.00000 99 0 47.7

## 6 8 NA 0.00000 94 0 62.8

## under.five.deaths Polio Total.expenditure Diphtheria HIV.AIDS GDP

## 1 83 6 8.16 65 0.1 584.2592

## 2 0 99 6.00 99 0.1 3954.2278

## 3 24 95 NA 95 0.1 4132.7629

## 4 98 7 NA 64 1.9 3695.7937

## 5 0 86 NA 99 0.2 13566.9541

## 6 9 93 NA 94 0.1 13467.1236

## Population thinness..1.19.years thinness.5.9.years

## 1 33736494 17.2 17.3

## 2 28873 1.2 1.3

## 3 39871528 6.0 5.8

## 4 2785935 8.3 8.2

## 5 NA 3.3 3.3

## 6 43417765 1.0 0.9

## Income.composition.of.resources Schooling

## 1 0.479 10.1

## 2 0.762 14.2

## 3 0.743 14.4

## 4 0.531 11.4

## 5 0.784 13.9

## 6 0.826 17.3

Simple linear regression

Linear regressions are used when we want to investigate relationships between variables. For example, in this case, imagine we want to investigate if overall life expectancy is related to the level of schooling of the country. This is different than in the previous activity, when we wanted to test if different groups had different means.

The lm() command creates a linear regression model. It takes the following format:

lm(response_variable ~ predictor_variables, data = data_source)

In this case, life expectancy is our response variable (i.e., we expect it to respond to the level of schooling), and schooling is our predictor variable (i.e., we expect it to predict life expectancy).

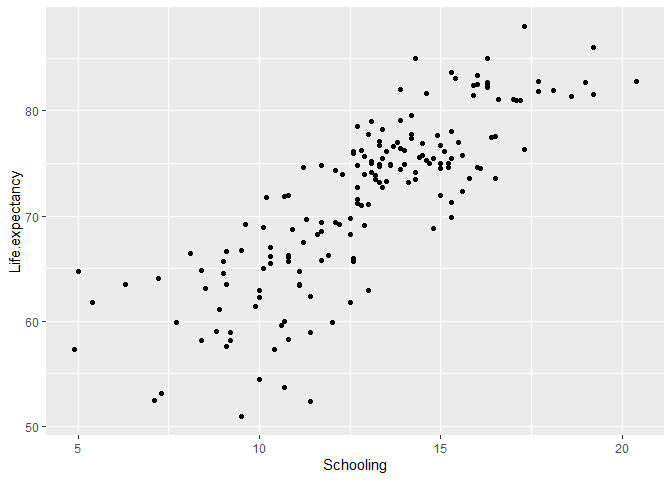

Visualize trends

To start, you first want to visualize the relationship in a plot to see if a linear relationship is reasonable. We will be using ggplot (part of the tidyverse package) to plot throughout this workshop. This was covered in the workshop Introduction to RStudio:

Type this in a code chunk and then send it to the command line:

# Create a scatter plot of life expectancy by Schooling

ggplot(data = life_expectancy_2015, # specify the data

aes(x = Schooling, y = Life.expectancy)) + # specify the variables

geom_point() # plot a scatter plot

Fit a simple linear regression

The plot shows that a linear relationship is reasonable. Therefore, we will create a simple linear regression model where the response variable is Life expectancy and the predictor variable is Schooling. The model can be written as:

life expectancy = intercept + slope * schooling

In R, type this in a code chunk and send it to the command line:

# Fit the model

lm_schooling <- lm(Life.expectancy ~ Schooling, data = life_expectancy_2015)

# See the results of the model

summary(lm_schooling)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = Life.expectancy ~ Schooling, data = life_expectancy_2015)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -15.909 -2.547 0.317 3.170 10.655

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 42.9016 1.5870 27.03 <2e-16 ***

## Schooling 2.2287 0.1198 18.61 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 4.575 on 171 degrees of freedom

## (10 observations deleted due to missingness)

## Multiple R-squared: 0.6694, Adjusted R-squared: 0.6675

## F-statistic: 346.2 on 1 and 171 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

There is a lot of information in this output:

-

Call: a reminder of the model you just fitted.

-

Residuals: a summary of the distribution of the residuals of the model. The residuals are the difference between the observed values and the value predicted by the model. You want this distribution to be normal, and comparing these values can help you inspect that, however, you will typically inspect this in other ways (see topic on assumptions below).

-

Coefficients: this is the main result of the model. It shows you the estimated values for the intercept and the slope (i.e., the slope for Schooling, in this case), the standard error of these estimates (i.e., the uncertainty around these estimates), and the results of a t-test (the t-value and the p-value associated with it) testing whether these values are significantly different from 0.

-

The small p-values for the coefficients (<0.001) indicate that the estimates for the intercept and slope are statistically significant. The specific values mean that we can write the model mathematically as: Life expectancy = 42.9016 + 2.2287 * Schooling.

-

The bottom part of the results gives you a summary of the overall fit of the model (i.e., how well the model explains your data). The most important are the R-squared, which tells you how much variance the model explains, and the results associated with the F-statistic, which tells you the significance of your entire model (and not just each individual coefficients, as the t-tests above show).

-

In this case, the R-squared value of 0.6694 indicates that 66.94% of the variance in Life Expectancy is explained by Schooling. The high R-square and the small p-value here (<0.001) tell you that this model is a good fit that explains a lot of variance in your data.

You might also want to get the 95% confidence interval for the coefficient estimates. Type this in a chunk of code and send it to the command line:

# Get confidence intervals of model estimates

confint(lm_schooling)

## 2.5 % 97.5 %

## (Intercept) 39.76897 46.034216

## Schooling 1.99229 2.465164

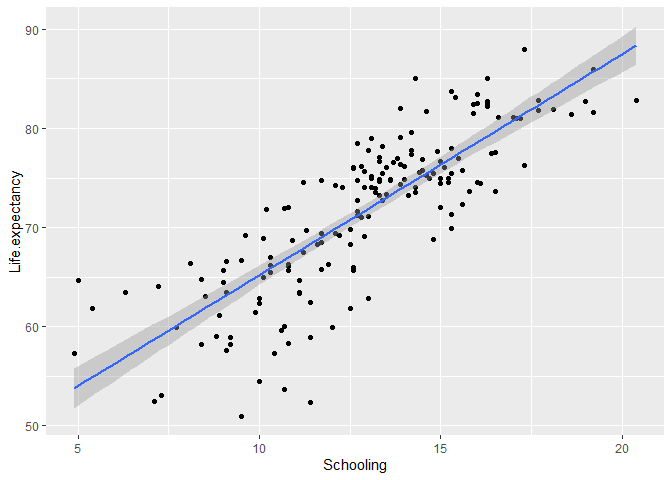

We can also visualize this model by adding a regression line to the plot. For that, type this in a chunk of code and send it to the command line:

# Create a scatter plot of life expectancy by Schooling with the fitted line of a linear regression

ggplot(data = life_expectancy_2015, # specify the data

aes(x = Schooling, y = Life.expectancy)) + # specify the variables

geom_point() + # plot a scatter plot

geom_smooth(method = "lm") # add a fitted line with confidence intervals using the linear model (lm) method

It seems like the line explains the trend in the data well. However, you will still want to check if the model meets the assumptions before you make any inferences from this model.

Assumptions

Linear regression makes several assumptions about the data, which form the acronym LINE: linearity, independence, normality, and equal variance of the residuals. To inspect these assumptions, you can use the function plot() on a lm object in R (i.e. the object with results of a linear model), which plots 4 useful diagnostics plots for regression models.

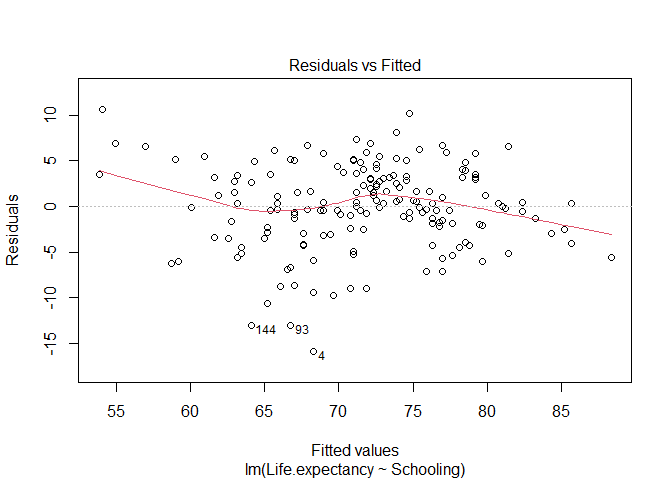

- Linearity: the model assumes the relationship between the variables is a linear relationship. You can check that visually in the scatter plot above. Another way to inspect is to plot the residuals of the model as a function of the fitted values (paste the code below in a chunk of code and then send it to the command line). If the relationship is linear, the line should be flat (i.e., observations are equally distributed above and below the line of fitted values of a linear model).

# Plot residuals versus fitted values

plot(lm_schooling, 1) # the number 1 tells R to plot the 1st diagnostic plot

The line is not perfectly flat, but it is reasonably close. Still, it suggests it might be good to examine the points with small and large fitted values as they seem to be the ones deviating from the flat line.

-

Independence: the model assumes each observation is independent of the others. Although there are ways to visually inspect this assumption if you have concerns about temporal or spatial non-independence, as we have seen in the previous section, usually this assumption is met by considering the structure of the data. In this case, we can reasonably assume that the countries are independent observations.

-

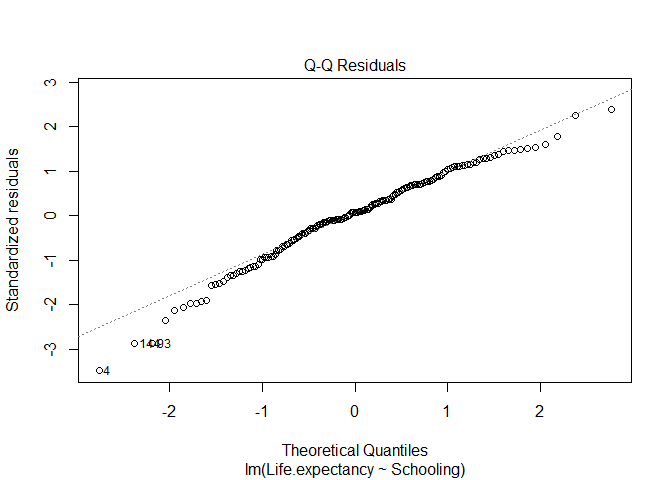

Normality of the residuals: the model assumes the residuals are normally distributed. To inspect this, you can check a Q-Q Plot of the residuals (paste the code below in a chunk of code and then send it to the command line). In this plot, the points should be close to the line (i.e. the line shows what would be expected for a normal distribution).

# Plot Q-Q plot of the residuals

plot(lm_schooling, 2) # the number 2 tells R to plot the 2nd diagnostic plot

Again, overal the points are close to the line, but there seem to be a few outliers. We may want to examine these data points in further analysis.

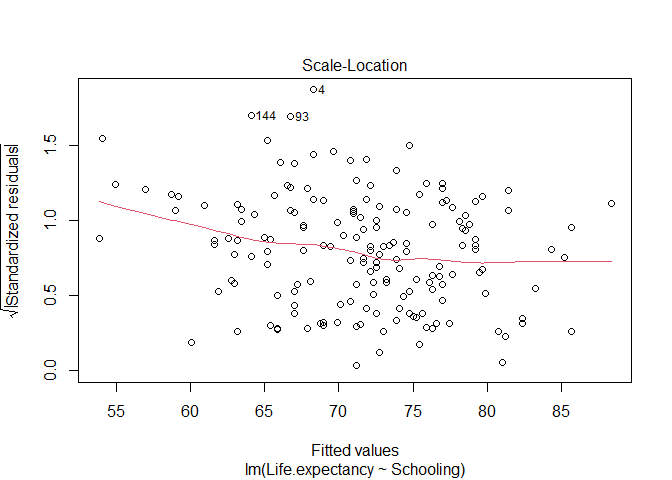

- Equal variance of the residuals: the model assumes the spread of the residuals around the fitted line (i.e. their variance) is the same for the entire range of the predictor variable. To inspect that, you can plot a scatter plot of standardized residuals versus fitted values (paste the code below in a chunk of code and then send it to the command line). Mainly, you want to check if this plot has a flat line, which would tell you the residuals have the same variance across the model.

# Plot Q-Q plot of the residuals

plot(lm_schooling, 3) # the number 3 tells R to plot the 3rd diagnostic plot

Again, the model seems to meet the assumption with a few outliers that might need to be examined further.

Multiple linear regression

Multiple linear regressions are very similar to simple regressions, but they contain more than one predictor variables. For example, we might want to expand our model to consider the simultaneous effect of schooling and an additional predictor variable, the average body mass index of the population (BMI).

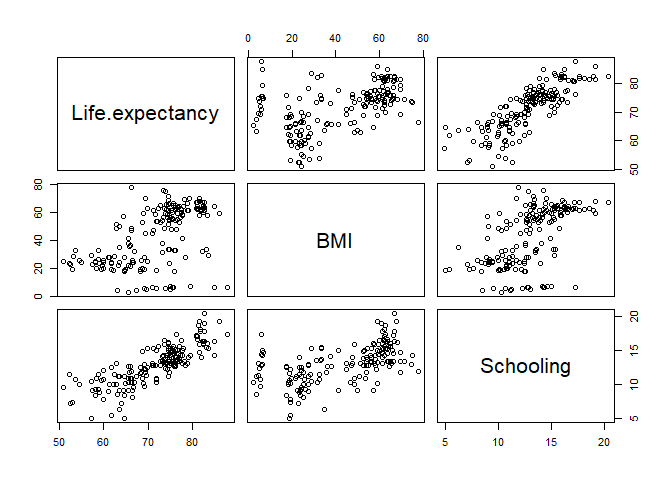

Visualize trends

First, let’s visualize the relationships. Type the code below in a chunk of code and then send it to the command line.

life_expectancy_2015 %>%

# Select the three relevant variables

select(Life.expectancy, BMI, Schooling) %>%

# plot pairwise correlation plots

pairs()

From the plot, BMI does not look as good as Schooling as a predictor of Life expectancy. But we will go ahead and fit a multiple regression model to have a concrete result.

Fit a multiple linear regression model

Create a multiple linear regression model where the response variable is Life expectancy and the predictor variables are BMI and Schooling. The model can be written as:

Life expectancy = slope_1 * BMI + slope_2 * Schooling + intercept

Type the following code in a chunk of code and send it to the command line to fit that model:

# Fit a multiple regression linear model

lm_multiple <- lm(Life.expectancy ~ Schooling + BMI, data = life_expectancy_2015)

# See the results of the model

summary(lm_multiple)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = Life.expectancy ~ Schooling + BMI, data = life_expectancy_2015)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -15.4768 -2.4894 0.1514 3.0108 11.2459

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 42.57196 1.66503 25.568 <2e-16 ***

## Schooling 2.16981 0.15029 14.437 <2e-16 ***

## BMI 0.02442 0.02045 1.194 0.234

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 4.569 on 168 degrees of freedom

## (12 observations deleted due to missingness)

## Multiple R-squared: 0.6677, Adjusted R-squared: 0.6638

## F-statistic: 168.8 on 2 and 168 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

As we thought, BMI is not a significant predictor variable with a p-value of 0.234. The model is still significant however, with p-value of 2.2e^-16, because Schooling is included. We conclude that the simple regression model adequately fits the data. For the sake of completeness, the multiple regression model can be written as:

Life expectancy = 2.16981 * Schooling + 0.02442 * BMI + 42.57196

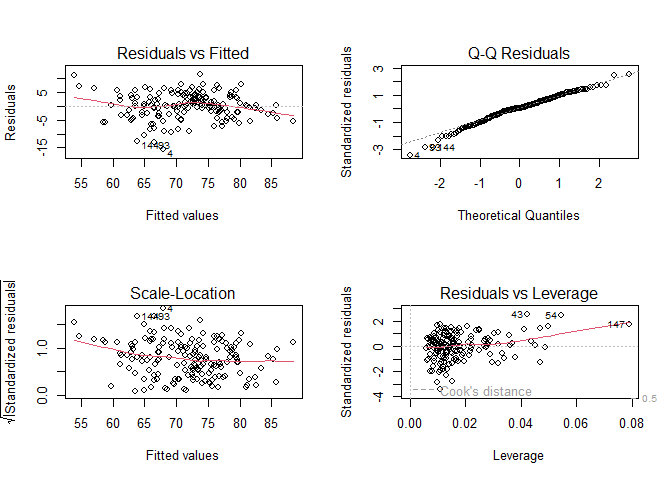

Assumptions

Similar to the simple model, this command produces graphs to check the model assumptions. Type the code below in a chunk of code and then send it to the command line.

# Changes plotting setting to create a panel with two rows and two columns to plot 4 graphs

par(mfrow = c(2,2))

# Plot the diagnostic plots (without number, R will plot all four plots)

plot(lm_multiple)

# Returns the settings for plots for single plot (one row and one column)

par(mfrow = c(1,1))

Again, the model does not seem to deviate much from assumtpions, but some outliers might be worth investigating further. The Residuals vs Leverage plot is helpful to identify outliers that might be affecting the model: they are shown with the number of observation right next to (i.e., in this case, observations number 43, 54, and 147 are outliers)

Conduct a single or multiple regression analysis with other variables of your choosing

You can now use the life_expectancy dataset to explore other relationships of your choosing. For that:

- Make a scatter plot to explore their linear relationship

- Build a linear regression model

- Assess the results. Let the instructors know if you need help!

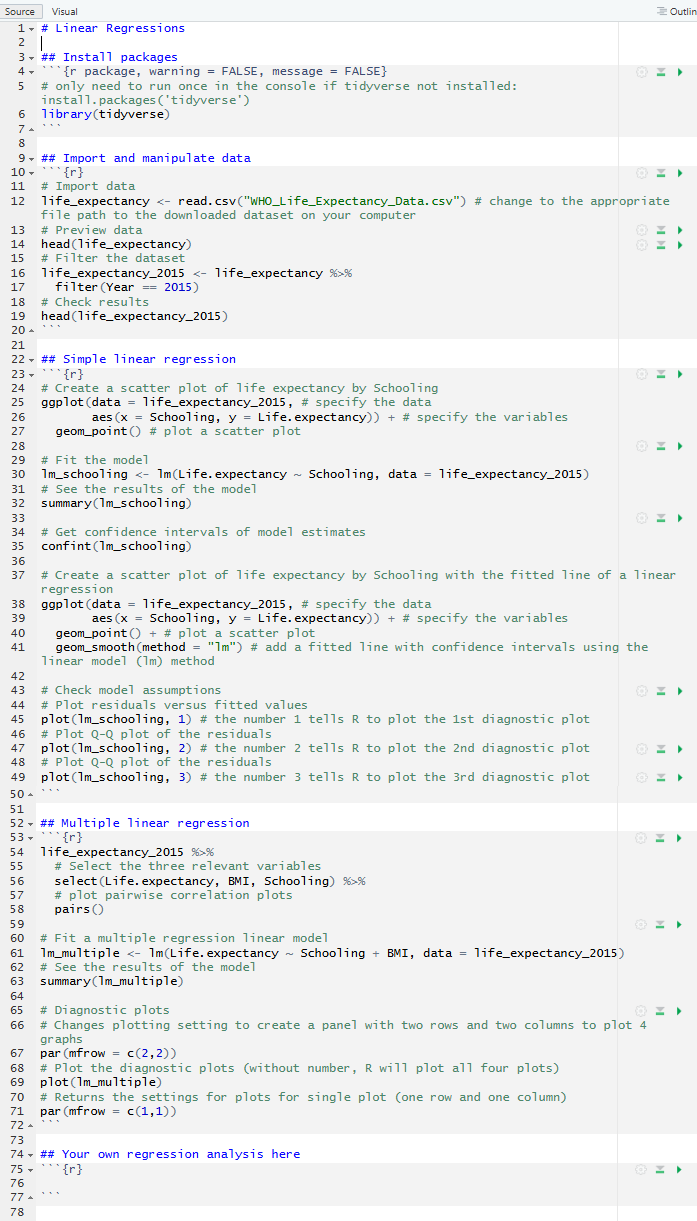

As the end of this activity, your Markdown file may look like this:

Again, knit this document into a .pdf and see how it looks!